Economic pressures jeopardize Connecticut's farming future

Marble Valley Farm in Kent leases land from the Kent Land Trust at below-market rates. The model enabled owner Megan Haney to grow her vegetable operation in an otherwise harsh economic climate for Connecticut farmers.

Sarah Lang

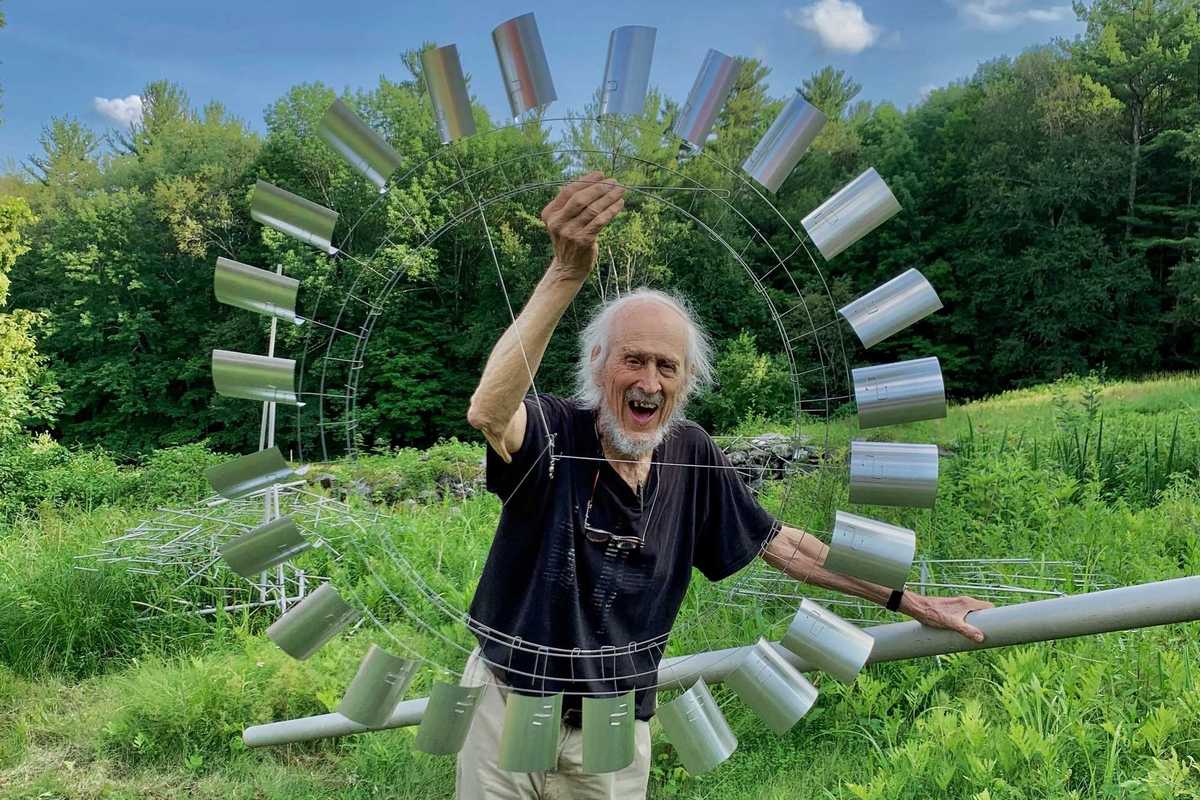

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO