McEnroe’s Organic Farm enters new era, teases plans to reopen market

Erich McEnroe standing in front of McEnroe Farms’ organic composting piles on the farm’s grounds at 194 Coleman Station Road in the Town of North East.

Photo by Aly Morrissey

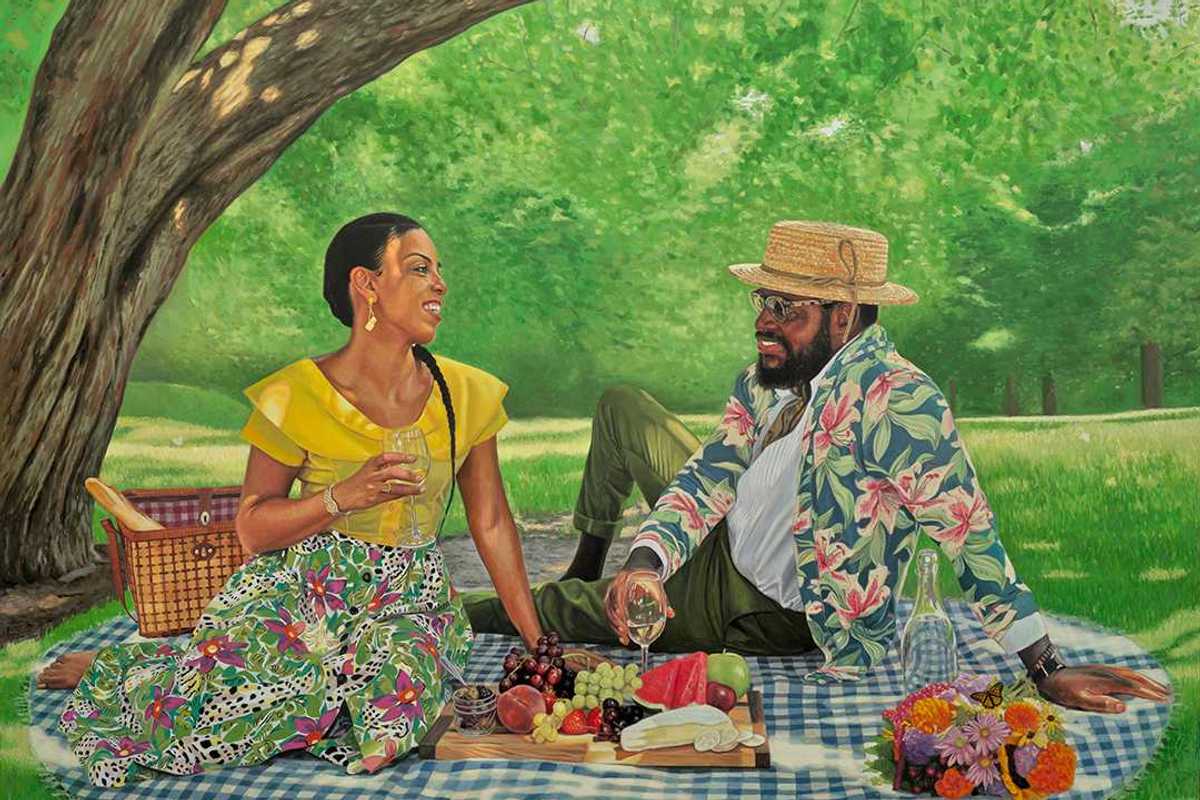

‘Sunkiss’ by Taha Clayton.Natalia Zukerman

‘Sunkiss’ by Taha Clayton.Natalia Zukerman ‘Crown Maker’ by Taha Clayton.Provided

‘Crown Maker’ by Taha Clayton.Provided

Matt and Bobby with customers at Dugazon.Jennifer Almquist

Matt and Bobby with customers at Dugazon.Jennifer Almquist

Jena Battaglia at No Comply Foods in Great Barrington, serving tomato garlic cream soup and artichoke grilled cheese sandwiches during Sunday brunch.Jennifer Almquist

Jena Battaglia at No Comply Foods in Great Barrington, serving tomato garlic cream soup and artichoke grilled cheese sandwiches during Sunday brunch.Jennifer Almquist Wedge saladJennifer Almquist

Wedge saladJennifer Almquist