Acknowledging Mohicans: Indigenous Land Back movement touches Copake

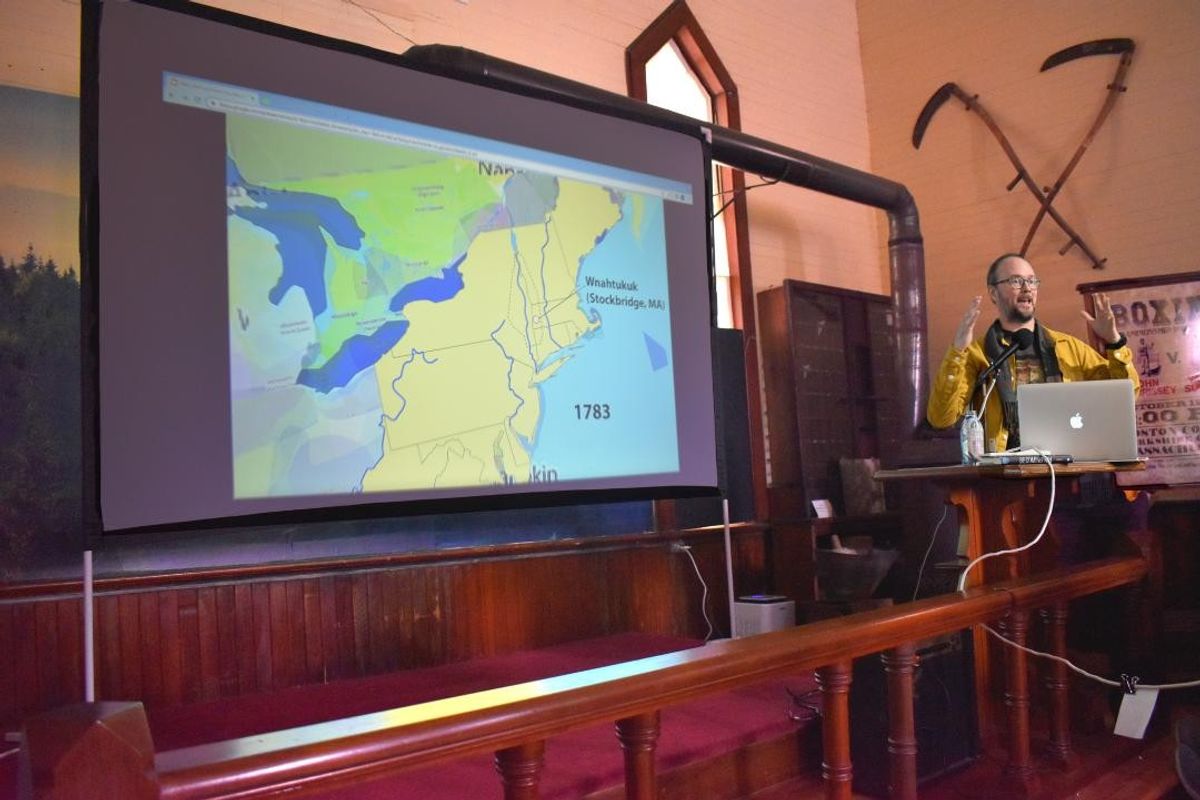

Bradley Pitts, Chair of the Mohican Allyship Committee of the Copake Town Board, shows a slide demarcating the Mohican ancestral homelands during his lecture, “Mohican Heritage: Past, Present, and Future,” at the Roeliff Jansen Historical Society in Copake Falls on March 17.

L. Tomaino

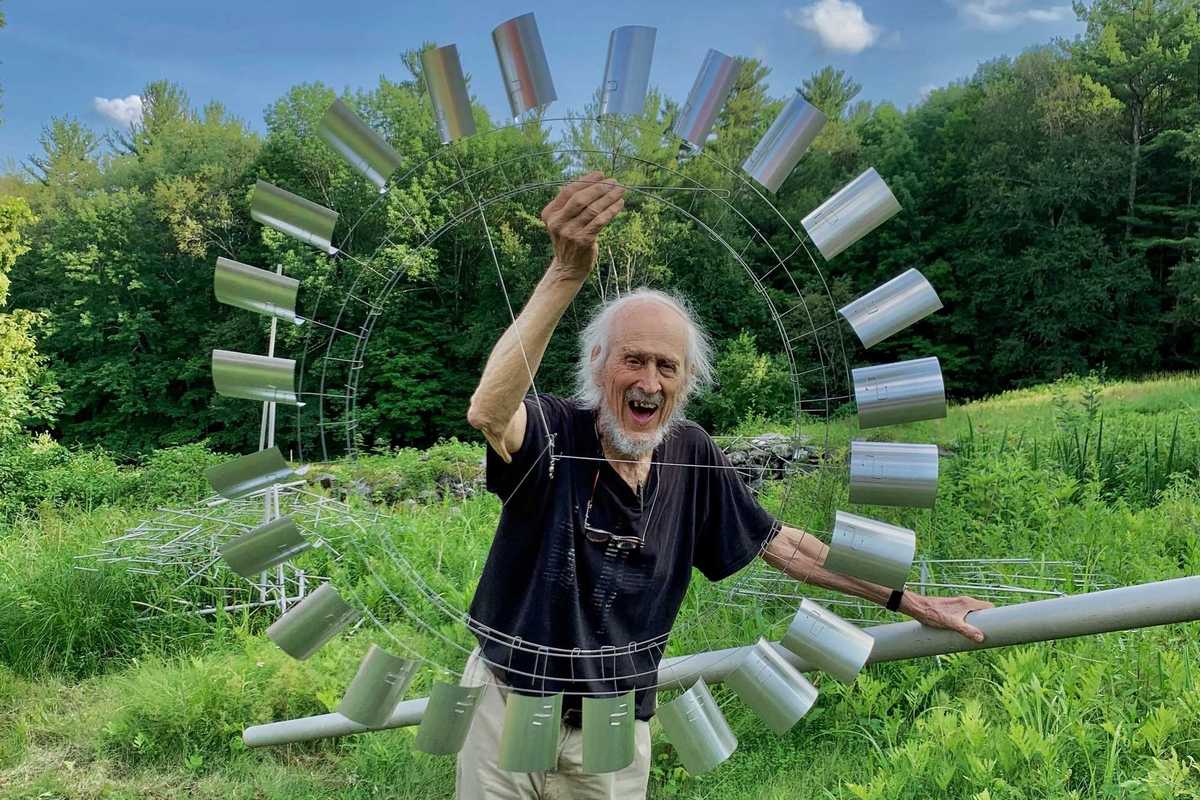

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO