Latest News

Living art takes center stage in the Berkshires

D.H. Callahan

Mar 04, 2026

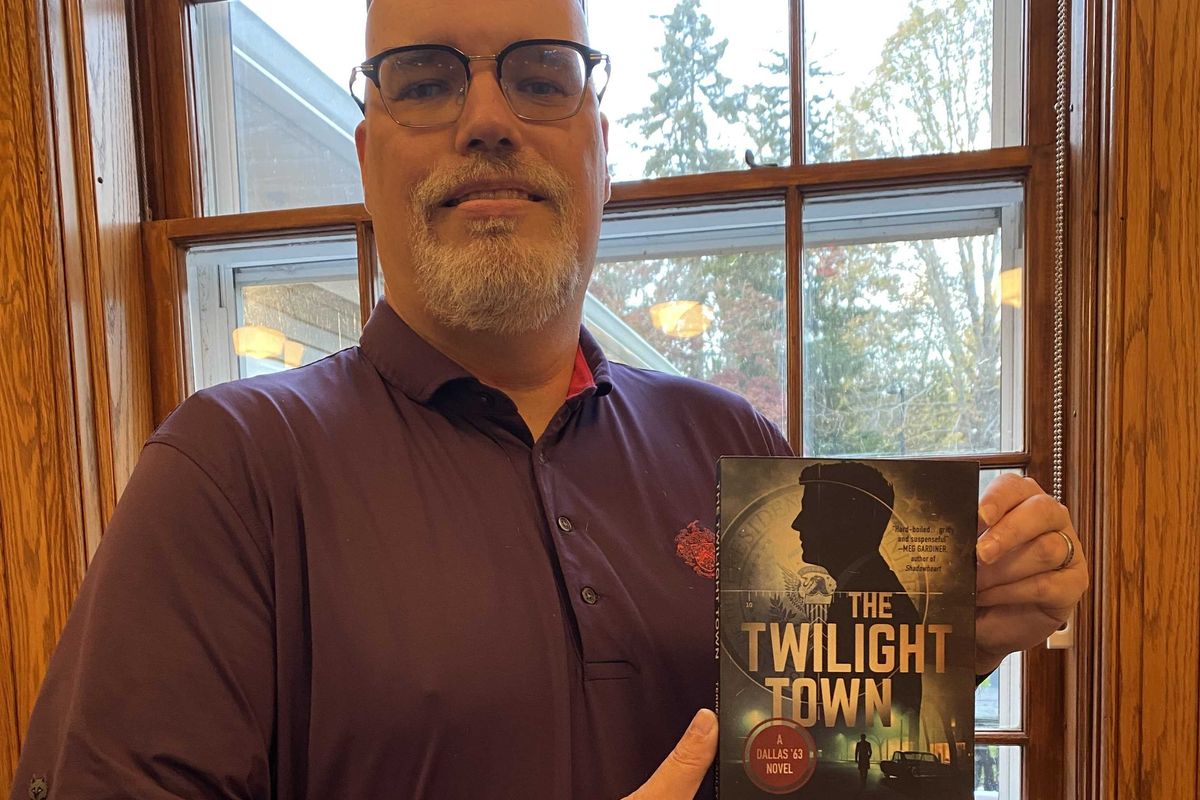

Contemporary chamber musicians, HUB, performing at The Clark.

D.H. Callahan

Northwestern Massachusetts may sometimes feel remote, but last weekend it felt like the center of the contemporary art world.

Within 15 miles of each other, MASS MoCA in North Adams and the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown showcased not only their renowned historic collections, but an impressive range of living artists pushing boundaries in technology, identity and sound.

MASS MoCA is known for its 20th-century holdings spread throughout a sprawling complex of industrial brick buildings. Installations by Sol LeWitt and James Turrell have permanent homes there. Just down the road in Williamstown, the Clark features masterworks by Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, John Singer Sargent and Claude Monet.

But what visitors might not immediately associate with those established names is how deeply both institutions invest in art happening right now.

On Saturday afternoon, a panel of young artists discussed their relationships with art, identity and technology as part of MASS MoCA’s “Technologies of Relation” exhibition, which opened that evening. The artists represented a broad range of cultural backgrounds, drawing on ancestry while exploring the future of art and technology.

The work itself ran the gamut: wax relief paintings, stained glass, interactive video and sculptural installations. One immersive piece automated the traditional Armenian practice of reading fortunes from coffee grounds. Particularly striking were Roopa Vasudevan’s hand-drawn QR codes and Taeyoon Choi’s large-scale weavings of binary code.

Opening the same night was Zora J. Murff’s “RACE/HUSTLE.” Through photographs, paintings and installations, Murff explores the wide-ranging and sometimes violent implications of being Black in America today. Each piece — whether confronting the rise of white supremacy or examining stereotypes imposed on Black communities — carries razor-sharp visual commentary designed to unsettle.

On Sunday, the Clark continued the contemporary thread. A small exhibition of work by Raffaella della Olga, titled “Typescript,” features intricate patterns created using a typewriter on varied paper surfaces. The effect seems almost impossible until viewers watch a video of della Olga loading her typewriter with 140-grit sandpaper and typing in a hypnotic rhythm. Though the typewriter is considered obsolete technology, she continues to find new applications for it, completing some of the works in recent months.

Next door in the Clark auditorium, HUB New Music performed works written specifically for its unusual instrumentation: violin, cello, clarinet and flute. While that combination may not stand out to casual listeners, relatively little classical repertoire exists for it. The ensemble regularly commissions composers to expand the possibilities.

The results were striking. From the opening notes of Francisco del Pino’s “Passacaglia,” the quartet’s command and layered repetition pulled unexpected emotion from the audience.

After three pieces came the world premiere of Daniel Wohl’s “Mirage,” a roughly 25-minute work accompanied by digital blips, static and electronic textures evoking radio transmissions and UFO lore. Hearing four virtuoso musicians extract entirely new sounds from traditional instruments echoed the weekend’s larger theme: old tools made new again.

Like della Olga’s typewriter, Vasudevan’s QR codes or Murff’s charged imagery, the performances demonstrated that contemporary art often grows from familiar materials — reimagined.

The old masters will always draw visitors to these institutions. But when living artists command equal attention, this quiet corner of the Berkshires feels less like the middle of nowhere and more like a creative epicenter.

D.H. Callahan is a voice actor, creative director and trail steward. He lives with his artist wife in West Cornwall, Connecticut.

Keep ReadingShow less

Persistently amplifying women’s voices

Aly Morrissey

Mar 04, 2026

Francesca Donner, founder and editor of The Persistent. Subscribe at thepersistent.com.

Aly Morrissey

Francesca Donner pours a cup of tea in the cozy library of Troutbeck’s Manor House in Amenia, likely a habit she picked up during her formative years in the United Kingdom. Flanked by old books and a roaring fire, Donner feels at home in the quiet room, where she spends much of her time working as founder, editor and CEO of The Persistent, a journalism platform created to amplify women’s voices.

Although her parents are American and she spent her earliest years in New York City and Litchfield County — even attending Washington Montessori School as a preschooler — Donner moved to England at around five years old and completed most of her education there. Her accent still bears the imprint of what she describes as a traditional English schooling.

Today, she and her family call Sharon, Connecticut, home. While she still travels frequently to Manhattan, she embraces the contrast between city and countryside.

“For me, it’s all about the contrast,” she said, adding that she is friendly and curious about people here in a way that doesn’t feel natural in the city. “I want to know who you are, what you do, and why you’re here. You end up meeting these really interesting people.”

As a longtime editor in newsrooms like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and Forbes, Donner said she began to notice something unsettling about how stories were framed, and whose voices were missing.

“It’s just the way news is done,” she said. “It’s the DNA of what we deem newsworthy and important in mainstream media.”

The problem, she explained, isn’t that women aren’t covered at all. It’s that when women are covered, it’s often in a stereotyped way. Women are frequently framed through familiar narratives – the gender pay gap, unpaid labor, caregiving – important issues that persist, she said, but are often treated as repetitive or secondary. Meanwhile, the stories deemed front-page worthy tend to revolve around power, economics, war and politics — and men.

“If we don’t make a deliberate effort to cover women, women won’t be covered,” Donner said.

The issue isn’t unique to any outlet, she stressed. “It’s just the way news is done.”

But that DNA — who gets quoted and whose experiences are centered — has consequences.

And for Donner, that realization demanded a response.

Enter The Persistent.

Founded in 2024, The Persistent was built around what Donner calls a simple but deliberate premise.

“Women don’t get covered in the same way men get covered,” she said.

The goal isn’t to exclude men or create a siloed “women’s section.” Instead, Donner said, it’s about correcting an imbalance by putting women at the center of the story.

Describing the approach as a reframe, this means expanding who is quoted as an expert. It means spotlighting women in business, politics, culture and global affairs. It also means examining major news stories through a lens that mainstream outlets often overlook.

“What we can add,” she said of The Persistent, “is perspective.”

Now approaching its second year — a milestone that will be celebrated next month — the publication operates with an all-women team of writers, editors and illustrators based across the world. The team meets regularly over Google Meet.

“They’re awesome,” Donner said of the editorial meetings. Some of her staff are mothers, some are not. All bring lived experiences to the table. Donner has intentionally created a newsroom culture that balances rigor with support.

“If your writing doesn’t measure up, I’m going to tell you,” she said plainly. “But it’s not a battle. It’s a partnership.”

Beyond publishing stories that matter, Donner wants contributors to be seen.

“I don’t just want people to read the story and forget who wrote it,” she said. “We can do a lot better if we amplify each other.”

As a woman, Donner rejects the idea that success is finite. She wants everyone to have a slice of the pie.

“Just make the pie bigger,” she said. “Bring more seats to the table. Make it richer.”

Donner credits her “mum” for articulating what would become her professional identity.

“You are what you can’t help doing,” her mother used to say.

Today, without hesitation, Donner said she can’t help being an editor.“My identity as an editor is very strong,” she said. Editing, she explained, is less about correcting typos and more about building and shaping ideas.

“Sometimes I imagine this physical movement of cracking something open,” she gestured.

That instinct traces back to childhood. She recalls sitting in a classroom around age 10, listening to a classmate read a short story aloud. For Donner, that moment crystallized something fundamental.

“Someone else’s words made me just sit up straight in my chair and think, wow, that is so good.”

Today, whether she’s in a historic manor house in Amenia or on a Google Meet with her team across the globe, that instinct remains the same: crack the story open, elevate the unheard voice and reframe the narrative.

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

Jarrett Porter on the enduring power of Schubert’s ‘Winterreise’

Natalia Zukerman

Mar 04, 2026

Baritone Jarrett Porter to perform Schubert’s “Winterreise”

Tim Gersten

On March 7, Berkshire Opera Festival will bring “Winterreise” to Studio E at Tanglewood’s Linde Center for Music and Learning, with baritone Jarrett Porter and BOF Artistic Director and pianist Brian Garman performing Franz Schubert’s haunting 24-song setting of poems by Wilhelm Müller.

A rejected lover. A frozen landscape. A mind unraveling in real time. Nearly 200 years after its premiere, “Winterreise” remains unnervingly current in its psychological portrait of isolation, heartbreak and existential drift.

Porter, praised by Opera News for his “imposing baritone” and “manifest honesty,” has built his career on major European opera stages, including Oper Frankfurt. But recital work, he says, is closest to his heart.

“I love to recital. If I were to pick my career, I would be doing some opera and mostly recital,” he said. “I think there can be difficulty with grabbing an audience in a recital, but this is one of the greatest pieces to do so because it is so psychological, so powerful, so universally moving.”

Unlike opera, there are no sets in a recital, no costumes or lighting cues to lean on. “The singer with no sets or costumes is left to create a kind of one-man show,” Porter said. His solution is internal. “The way that I process learning something like this and having the responsibility to hold an audience without set or costumes or lights or props is to stage it in my mind. Each song has an identity.”

Schubert’s writing, Porter insists, needs no adornment. “Schubert does an amazing job at setting the scene, and for me, you don’t need anything else. I feel like anything added to it would be almost subtracting. I’d rather just see the singer and the pianist the way that Schubert intended it to be.”

At the center of “Winterreise” is the wanderer, an unnamed figure moving through snow and memory after a failed love affair. For Porter, the character is both specific and universal. “There’s so much ambiguity in the piece,” he said. “We don’t know all of the answers in the first song. We don’t really know who this person is. There are tidbits of information dropped throughout each song. And I think the tendency is to put a narrative on that and to try to connect the dots rather than embracing what it is. The ambiguity is actually where the beauty is.”

That ambiguity extends to the cycle’s ending and the encounter with the eerie hurdy-gurdy player in “Der Leiermann.” Does the protagonist die? “I think one could make that argument,” Porter said. But he resists a neat conclusion. “Death is right in front of him. Death is actually the most peaceful answer to his problem and it’s not given to him. There’s something more, a deeper level.”

Rather than a literal death scene, Porter sees a reckoning. “For me, he’s not granted the easy way out. He has to sort of come to terms with being nothing and having no real skill as a songster or a poet or a wanderer.” The winter landscape, he suggests, mirrors the psyche: “The winter is sort of the mirror of his heart.”

In shaping the emotional arc across all 24 songs, Porter leans into uncertainty rather than resolution. “What I relate to in this piece is that in life, you don’t know what’s going to happen. And you don’t know the next day. Even in tragedy—especially in tragedy—there’s so much question.”

Porter performed Gounod’s “Faust” at BOF in 2024 with Garman conducting but this will be the first time the two will be collaborating with Garman at his instrument. “I love making music with Brian,” said Porter. “I’m a huge fan of his musicianship. I think we’re sort of bitten by the same bug that Schubert is, and so I was super honored that he asked me to do this with him.”

For tickets, visit berkshireoperafestival.org

Keep ReadingShow less

A grand finale for Crescendo’s 22nd season

Sally Haver

Mar 04, 2026

Christine Gevert, artistic director, brings together international and local musicians for a season of rare works.

Stephen Potter

Crescendo, the Lakeville-based nonprofit specializing in early and rarely performed classical music, will close its 22nd season with a slate of spring concerts featuring international performers, local musicians and works by pioneering composers from the Baroque era to the 20th century.

Christine Gevert, the organization’s artistic director, has gathered international vocal and instrumental talent, blending it with local voices to provide Berkshire audiences with rare musical treats.

“The biggest event of this part of our season is our April 25 and 26 concerts, with the US premiere of ‘A Jewish Cantata’ and the iconic ‘Misa a Buenos Aires,’” said Gevert. “The composer, an internationally renowned musician, will come and share the podium with me.”

Among the other season highlights are concerts showcasing the works of two trailblazing female musical innovators, Francesca Caccini, the early Baroque composer, poet and singer; and Wanda Landowska, the 20th-century virtuoso who single-handedly brought the harpsichord back from obscurity. Also not to be missed is the May 30 concert, Bach’s Motets in Concert, featuring all six of Johann Sebastian Bach’s surviving motets, sung by four eight-part double choruses and accompanied by period instruments, widely considered the pinnacle of Baroque choral music.

For a schedule of concerts and tickets, visit crescendomusic.org

Keep ReadingShow less

NECC ‘Craft Collective’ offers space to create

Aly Morrissey

Mar 04, 2026

Ash Baldwin, senior administrative assistant at the North East Community Center, launched the weekly Craft Collective in July 2025.

Photo by Aly Morrissey

MILLERTON — A new low-key crafting group at the North East Community Center (NECC) is giving locals a reason to finally finish those half-started projects, providing a space for craft lovers to work in community and exchange tips and tricks.

The weekly “Craft Collective,” – launched in July 2025 by staff member Ash Baldwin – invites community members to bring their own crafts and work alongside others in a casual, social setting. The free program is part of NECC’s broader effort to offer accessible, community-building programming.

“I’m the type of person who struggles to stay focused on projects,” said Ash Baldwin, NECC’s senior administrative assistant, who came up with the idea last summer. “I realized I work better when I’m with other people and when I have a dedicated time and space.”

The idea took shape after Baldwin found herself racing to finish a crocheted baby blanket for her sister’s baby shower.

Participants have already brought a range of projects to the group, from sewing and mending to creative repurposing – including one crafter who transformed an old shower curtain into kitchen valence curtains.

“The goal is really community and connection,” Baldwin said. “People can meet other crafters, swap tips, give feedback on projects – maybe even make a friend.”

Crafting, Baldwin said, offers a kind of mental reset. “It’s peaceful,” she said. “It quiets my mind and lets me focus on one thing at a time.”

Like many crafters, Baldwin admits to having yarn and unfinished projects scattered around her home, and says she tends to make gifts for others more than items for herself.

Though Baldwin has been crocheting since 2022, creativity has always been part of her life. Her mother sews, her grandmother crocheted, and she grew up surrounded by creative projects. Baldwin joked that her grandmother once “fully kidnapped” her American Girl doll to make custom clothes for it. She also describes herself as a longtime “band kid,” saying creative arts were woven into her childhood.

When she’s not organizing the Craft Collective, Baldwin works behind the scenes at NECC, handling administrative and fiscal operations, including service tracking for programs such as the food pantry.

The Craft Collective is held every Tuesday at 6 p.m. at 51 S Center St., Millerton. There is no cost to participate. For questions or to donate crafting supplies, contact Ash Baldwin at ash@neccmillerton.org or (518) 789-4259 ext. 132.

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

loading