When girls ran the Moviehouse

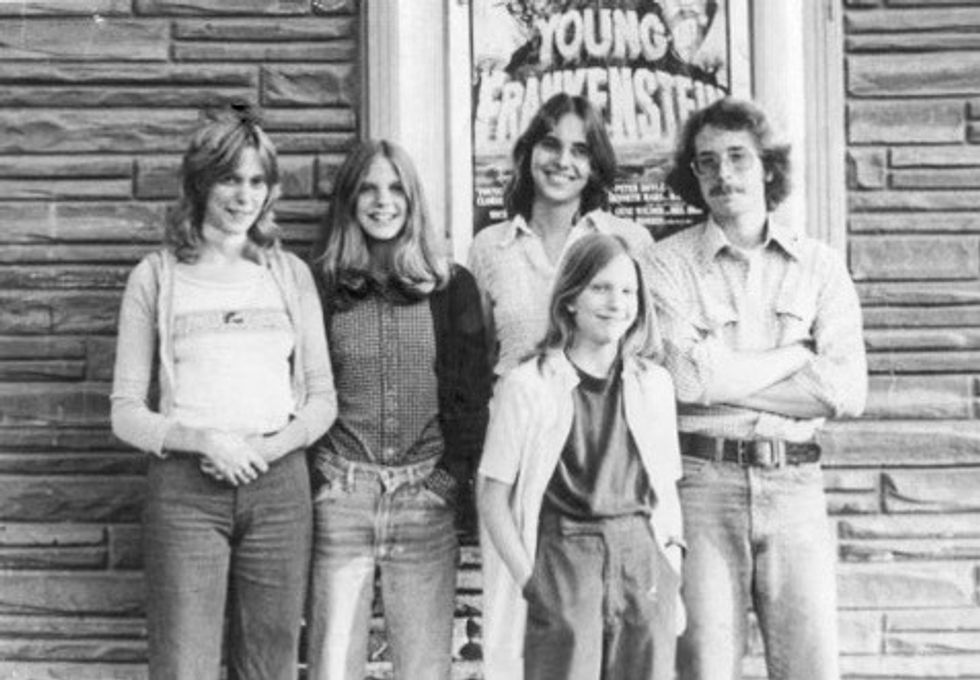

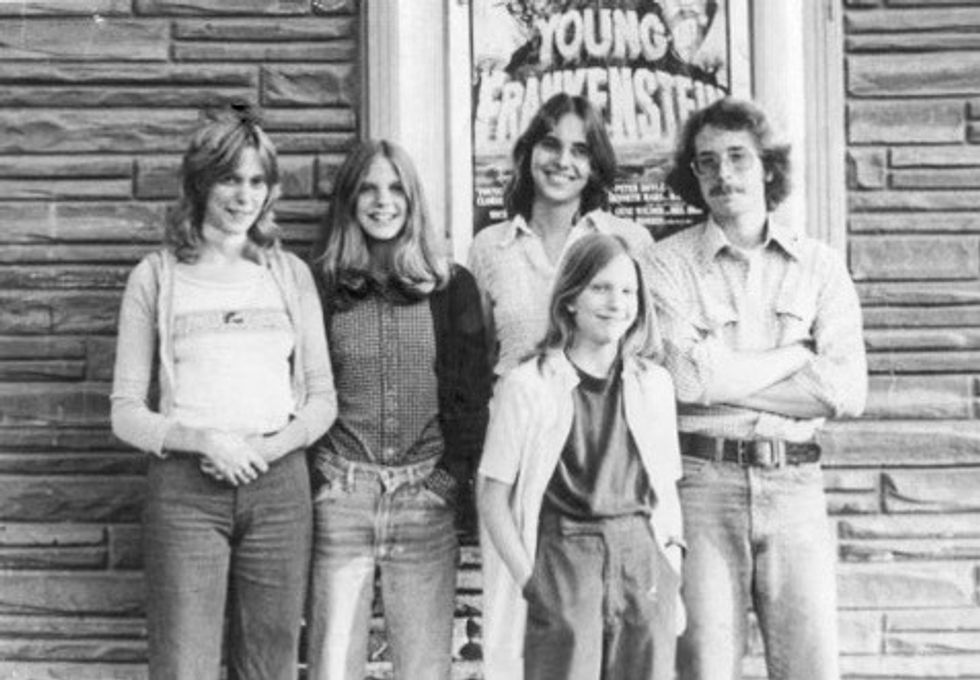

From left, Laura, Marcia and Sharon Ferguson, Tom Babbitt, and (in front) Sandy Ferguson, pose in front of the Millerton Moviehouse — then called The Millerton Theater — in 1974. Photo courtesy of the Fergusons

MILLERTON — The Moviehouse on Millerton’s Main Street is iconic.

Built in 1903 and used briefly as a grange hall, it was soon converted into a movie theater with a second-floor ballroom. Some know that it fell into disrepair in the 1970s before being bought and restored by Carol and Robert Sadlon in 1977. Some fewer know that it was briefly a porn theatre. But it is a seldom told story that, for two years (the summers of 1974-1975), four teen-aged sisters ran the movie theater.

The girls’ father, M. Carr Ferguson, senior counsel in Davis Polk & Wardwell’s tax department, was teaching at the University of Iowa in the early 1960s when he was offered a position at New York University Law School. His beloved late wife agreed to the move on one condition: that they’d also have a place in the country.

One of their four daughters, Sharon, recalled: “Mom told me that she put a map out and placed a pin right where we lived. She then cut a string as long as what would have been 100 miles, and she just ran the string around. Anywhere within that space was okay. Turned out Lakeville was it!”

The Fergusons sent their children to PS 41 in the city and raised them in Washington Square, but summers were always spent up at the lake. As the children got older, however, it got harder and harder to entice them away from their social lives and the allure of the city. Then Mrs. Ferguson had an idea.

Mr. Ferguson recalled her saying, “We have to do something to get the girls up here, and we can get rid of the adult movie house at the same time.”

At the time, the Millerton movie house (called the Millerton Theater prior to 1978) was a porn theater.

In December 1973, The Lakeville Journal ran a story reading:

“‘Are you aware of the type of motion picture you are coming to view?’ Richard Masters asks this of everyone who comes to purchase a ticket for the XX-rated movies in Millerton, N.Y. Apparently some people have different expectations and do not realize the type films that are being shown.

“Richard and Barbara Masters, formerly employed at the Canaan Drive-in in Connecticut, took over as managers of the Millerton theatre on Monday Nov. 26. The Victory Theater Corporation, which bought the Millerton Theater back in June, can explain the run of sex-based movies.

“Jim Severin, spokesman for Victory, said. ‘No theater goes to X policy through preference, only through darn necessity.’ According to Mr. Severin, the Millerton Theater has lost over $5,000 since August: ‘at this point we’re just looking to meet house expenses. With X-rated films our take is a little bit better.’”

In the early ‘70s, Mr. Ferguson had a client in the United Artists theater corporation. That client was Egyptian-born Salah M. Hassanein, who began his career as an usher at a movie theater in New York and rose through the ranks to become president of United Artists Eastern Theaters and subsequently president of Warner Brothers International Theaters.

In the summer of 1975, The Fergusons decided they would rent the movie house from the Victory Theater Corporation with motivation that was two-fold: to stop the showing of the X-rated movies and to entice their four daughters to spend their summers with the family in Lakeville.

For the next two summers (1974-1975), the four Ferguson daughters, aged about 11-19 at the time, ran the theater.

“At the beginning, they didn’t like us,” said Marcia, referring to the men in town who had frequented the porn showings.

“At the beginning, bras and tampons got thrown into the lobby because it was four girls running the theater!” The sisters laughed, and Marcia continued, “Laura, my oldest sister, had the idea to take advantage of all the male attention and would get them to help sweep the lobby. The next thing you know, they were our ‘protectors.’”

The girls came up with all sorts of ways to entice the men to their advantage because, as it turned out, running the theater was a huge job.

“Laura, the oldest, was the manager,” explained Marcia. “Sharon sold tickets and made popcorn, and I was the projectionist.”

A young man in town, Jason Schickele, who had worked as the projectionist at the Mahaiwe and Colonial theaters, showed Marcia, 14 years old at the time, how to run the projectors.

“He was patient,” Marcia said, showing her again and again everything about the machine. “You were running celluloid,” she explained, “So you’d watch for the little dot in the right-hand corner called ‘the changeover,’ and when you saw that, there was a second dot. That’s when you had to change the film.”

She continued, “If there was a crack in it, you could fix it with just, you know, regular old scotch tape, but you’d have to run it with a little viewfinder so you could see where the problem was.”

She continued: “It was really fun to work those machines. I mean, they were elaborate. You would bang together the carbon. It might take a few times for it to light, but when it did, you couldn’t really look at it. It’s like looking at the sun. It was so powerful.”

“We had so many mishaps,” Sandy laughed.

Marcia continued: “Jason saved our bacon so many times. We would have a full house, having sold all these tickets, and the thing would break, and I’d be completely panicked. Then he’d come over and help us.”

When asked which years they ran the theater, there’s a lot of back and forth about whether it was ‘74-’75 or ‘75-’76.

“I try to set the memory of that time by the movies that we showed because Salah gave us second-run movies. We were a couple of weeks behind,” said Sandy.

“It was movies like ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail,’ ‘Young Frankenstein,’ ‘Jaws,’” said Sandy, with Marcia jumping in: “One of the really popular ones was when they gave us ‘Gone with The Wind.’”

“That was the very first movie we showed,” Mr. Ferguson interrupted, returning to the busy kitchen from another room in the house. He went on to proudly say, “These girls had it running at a profit for those two summers.”

The girls had constantly evolving, entrepreneurial ideas of how to make it a sustainable business, and the theater was a success.

“We placed ads in the paper all the time,” said Marcia, “like ‘Thursday dollar night.’ When it rained, if we woke up and it was raining, we’d call the summer camps and say, ‘bring the campers,’ and we’d go run whatever we were running.”

“We made a profit,” Marcia continued. “And at the end of the two years, I got a stereo system.”

In returning to the origin of the idea, Marcia said: “Mom was in it to get us home for the summer. I mean I was 14 so I was gonna be home anyway, because we didn’t have money for camp. We were not camp kids. This was our camp.”

When asked why they didn’t continue, Mr. Ferguson said that after the two initial summers, they floated the idea around of buying the theater. He explained that he “wanted to buy it, but Marianne [his wife] said, ‘Carr, the kids are graduating. They’re not gonna run it. I’m not gonna run it. You’re not gonna run it.’”

The space lay empty again until Bob and Carol Sadlon purchased it in October 1977, renovating and opening it once again in 1978.

“There’s such a wealth of documentation now with our phones,” said Carol Sadlon when asked about the state of the theater when she and her husband purchased it. “But it’s too bad there isn’t more of the way it was then.”

She went on to say: “It was a single theater with 300 seats. There was no heat, no air conditioning. It was in just terrible condition.”

She said: “Laura [Ferguson] and I had a wonderful conversation years ago, as I recall, because we were both very interested in the preservation of theaters like the Moviehouse, of course. [The Fergusons] have so much enthusiasm, and it really is just extraordinary what they were able to do.”

Several of the Ferguson women have gone on to have lives in performance. Marcia recently retired from the theater department at the University of Pennsylvania and has performed in numerous films and in theater; Sandy (now Huckleberry) is an artist with the Boston-based artists’ collective Mobius.

The Moviehouse again closed its doors in March 2020, until its highly anticipated reopening by David Maltby and Chelsea Altman, who have managed to honor the Moviehouse’s history while bringing a new energy and vision to the space.

PINE PLAINS — The Pine Plains FFA Ag Fair brought a crowd to the high school on Church Street Saturday, Oct. 11.

Kicking off the day was the annual tractor pull, attracting a dedicated crowd that sat in bleachers and folding chairs for hours watching Allison-Chalmers, International Harvesters and John Deeres compete to pull the heaviest weights.

A large collection of food was on offer from the Pine Plains FFA and each one of the classes in the Pine Plains Central School District. The football team was selling pickles.

Stissing Mountain High School Principal Christopher Boyd enjoyed a dip in the dunk tank to raise money for the Pine Plains teachers’ union-sponsored scholarship.

The Rev. AJ Stack, center right, blessing a chicken at the pet blessing event at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Amenia on Saturday, Oct. 4.

AMENIA — After serving more than five years as Priest-in-Charge of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Amenia, the Rev. AJ Stack announced Tuesday, Oct. 7, that he will resign from the church and Food of Life/Comida de Vida pantry. His last day at his current post will be Sunday, Nov. 2, the conclusion of the Feast of All Saints.

The news was shared in two emails from Stack — one to Food of Life pantry subscribers and volunteers, and another to parish members.

“I write tonight with difficult news, and I wanted you to hear it from me as soon as the Vestry and I had a chance to meet,” he wrote. “After much prayer and careful discernment, I have submitted my resignation to the Vestry as Priest-in-Charge of St. Thomas, and therefore as Executive Director of Food of Life/Comida de Vida.”

Stack provided few details about his departure. At time of publication, he had not announced his next steps but said the decision was “not sudden,” and followed careful consideration over a period of months. He will not be leaving the area or the diocese.

An announcement about his path forward and the transition process is expected soon. In the meantime, Stack said he remains “fully present” at the church, and the food pantry services will continue without interruption.

Stack expressed gratitude for the community and the growth of St. Thomas’ mission during his tenure. “Together we have welcomed new neighbors and strengthened our outreach in meaningful ways,” he said. “I trust that good work will continue.”

He joined St. Thomas in March 2020 and guided the church and community through the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent interview with The News about the food pantry, Stack estimated that it serves 653 individuals from 156 households each week, highlighting a significant contribution to the community.

The announcement was met with messages of reassurance from pantry volunteers. Jolly Stewart, a Vestry member and volunteer, wrote to the community with words of reassurance following the announcement. “I have complete faith in the strength of the parish of St. Thomas,” she wrote. “Our history shows how we have done this time and again, each time becoming more than what we were before. We can, without a doubt, do this now.”

MILLERTON — Ten candidates for office in the Nov. 4 election will answer questions from Dutchess County voters at a candidate forum on Friday, Oct. 24, at the Annex at the NorthEast-Millerton Library located at 28 Century Blvd.

The forum, which is sponsored by the library, will be held from 6 to 7:30 p.m.

Candidates for local and county offices will answer questions from residents in attendance or from residents who have submitted questions in advance.

“We’re excited to keep the tradition of the candidate forum going,” said Rhiannon Leo-Jameson, director of the library. “Some years we can’t always get candidates together.”

This year’s forum will include:

Rachele Grieco Cole, a democrat, and Chris Mayville, a republican, who both are running uncontested for the North East Town Council;

Casey McCabe, a democrat, also running uncontested for North East Justice.

Among Dutchess County races:

Tracy MacKenzie, who is endorsed by Republicans and Democrats,is running uncontested for Dutchess County Family Court Judge;

Kara Gerry, a democrat, and Ned McLoughlin, a republican, are in a contest for a Dutchess County Court judgeship currently held by McLoughlin.

Chris Drago, D-19, and Tonya Pulver, a republican, are competing to represent Dutchess County’s19th District seat currently held by Drago.

Democratic incumbent Dan Aymar-Blair and Will Truitt, the republican chair of the county legislature, are competing for the Dutchess County Comptroller position currently held by Aymar-Blair.

Leo-Jameson is encouraging questions for the candidates to be submitted in advance, which will not be revealed to candidates beforehand. Dutchess County residents may pose questions during the forum. To submit a question on the library’s website, go to the calendar at nemillertonlibrary.org and find the link in the Oct. 24calendar entries.

The format calls for opening statements from the candidates, followed by questions from residents, and candidates will be able to stay after the forum to answer questions personally.

The residence at 35 Amenia Union Road in Sharon was damaged after being struck by the Jeep Grand Cherokee around 3 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 11.

SHARON, Conn. — Emergency crews were called Saturday, Oct. 11, to Amenia Union Road in Sharon for a report of a vehicle into a building with entrapment.

Connecticut State Police reported Charles Teti, 62, was driving his Jeep Grand Cherokee northbound on Amenia Union Road when, for an unknown reason, the vehicle veered across the southbound land and exited the roadway where it struck a tree and home. Airbags deployed.

Teti and front seat passenger Aidan Cassidy, 63, sustained serious injuries. Teti was airlifted to Hartford Hospital and Cassidy was transported by ambulance to Sharon Hospital for treatment.

Back seat passenger Shea Cassidy-Teti, 17, sustained fatal injuries and was pronounced dead on scene. Cassidy-Teti was a senior at Kent School. He played on the football and tennis teams.

The residence that was struck is located at 35 Amenia Union Road.

The case remains under open investigation. Witnesses are asked to contact Trooper Lukas Gryniuk at Troop B 860-626-1821.