Dealing with invasive species

Sam Schultz, terrestrial invasive species coordinator with PRISM, is holding a tool she calls a “best friend” in the battle against invasives: the hand grubber. She was one of the presenters at the Copake Grange for a talk about invasive species Saturday, March 2.

L. Tomaino

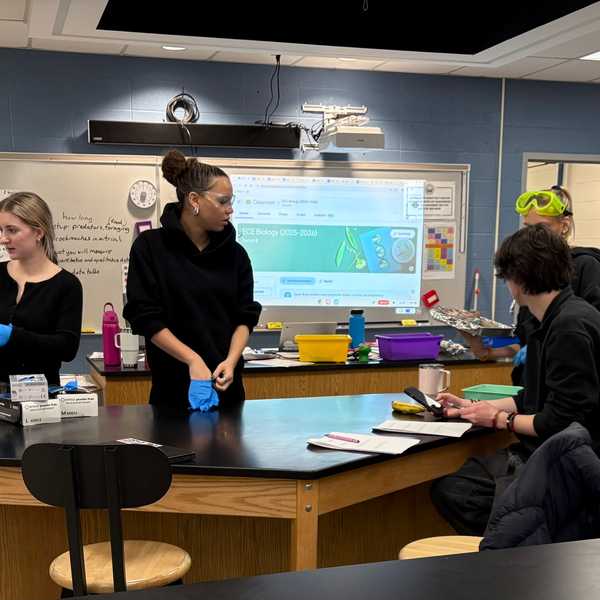

Local parents, child care providers and nonprofit representatives outline the challenges they face in accessing and providing childcare in rural northeast Dutchess County during a forum at the Stissing Center in Pine Plains on Wednesday, Feb. 25. Photo by Nathan Miller

Local parents, child care providers and nonprofit representatives outline the challenges they face in accessing and providing childcare in rural northeast Dutchess County during a forum at the Stissing Center in Pine Plains on Wednesday, Feb. 25. Photo by Nathan Miller

lakevillejournal.com

lakevillejournal.com

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino