Latest News

The Millerton 175th anniversary committee's tent during the village's trunk-or-treat event on Oct. 31, 2025.

Photo provided

MILLERTON — As Millerton officially enters its 175th year, the volunteer committee tasked with planning its milestone celebration is advancing plans and firming up its week-long schedule of events, which will include a large community fair at Eddie Collins Memorial Park and a drone light show. The events will take place this July 11 through 19.

Millerton’s 175th committee chair Lisa Hermann said she is excited for this next phase of planning.

“As we enter our anniversary year, there is a clear sense of excitement throughout the village and surrounding communities,” Hermann said. “Local businesses and organizations have been eager to get involved and help make this a truly special event for our community.”

Throughout 2025, committee members attended local events and gatherings to promote the celebration and hear ideas from businesses and residents.

Hermann said momentum continues to build as the committee works to finalize details and ensure the celebration honors Millerton’s rich history while remaining fun and engaging for all ages.

“It has been especially meaningful to hear longtime community members share stories from past celebrations and reflect on their cherished village memories,” she added.

In the months ahead, organizers plan to finalize vendors, secure additional sponsors, and continue spreading the word. Submissions are now open for musical acts, food truck vendors and sponsors wanting to promote their business while offsetting the cost of hosting such an event. Several sponsorship opportunities are available, including support for fair elements such as a stage, tent, activation and more.

The committee is also working with local businesses, including The T-Shirt Farm, to stock branded anniversary merchandise. Marketing efforts have increased, and members plan to attend more community events and seek opportunities to spread the word on TV, radio and printed materials.

Locals and visitors can follow updates on the committee’s Facebook page, which is beginning to reveal a schedule of events packed with family-friendly fun. Organizers hope people will share the page widely as a one-stop-shop for event information.

“This week-long celebration is shaping up to be another unforgettable chapter for our community,” Hermann said. “We hope the event itself will become one of the many memories that make Millerton such a wonderful place to call home.”

Keep ReadingShow less

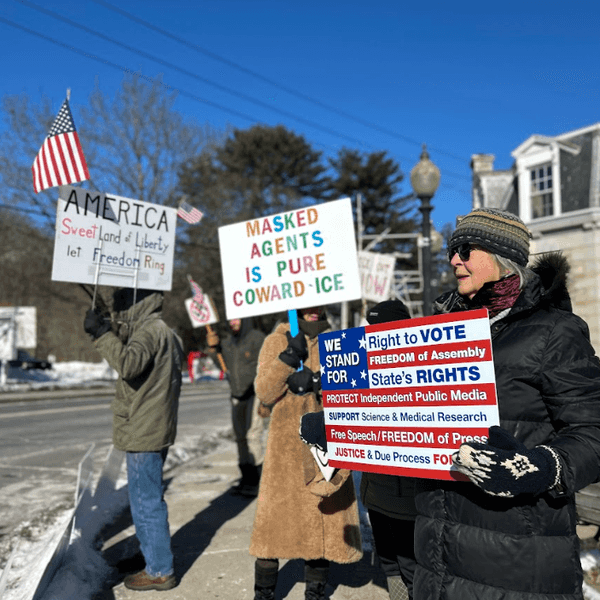

A small group of protesters voice opposition to President Trump's administration and Immigration and Customs Enforcement at Amenia's Fountain Square at the intersection of Route 44 and Route 22 on Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025

Photo by Nathan Miller

The fatal shooting of Alex Pretti, and before him Renée Good, by federal agents in Minnesota is not just a tragedy; it is a warning. In the aftermath, Trump administration officials released an account of events that directly contradicted citizen video recorded at the scene. Those recordings, made by ordinary people exercising their rights, showed circumstances sharply at odds with the official narrative. Once again, the public is asked to choose between the administration’s version of events and the evidence of its own eyes.

This moment underscores an essential truth: the right to record law enforcement is not a nuisance or a provocation; it is a safeguard. As New York Times columnist David French put it, “Citizen video has decisively rebutted the administration’s lies. The evidence of our eyes contradicts the dishonesty of the administration’s words.”

Separately, law enforcement agencies across the country are expanding their capacity to watch the public. Here at home, as we’ve reported, Dutchess County’s Real Time Crime Center brings together feeds from automated license-plate readers, including systems provided by Flock Safety, allowing police to track vehicles across jurisdictions in real time. These tools collect detailed movement data on vast numbers of people who are not suspected of any crime, often with limited public discussion of safeguards or oversight.

When citizens document state power, they are told to step back or trust official explanations. When the state documents the public, continuously and at scale, it is framed as efficiency. One form of observation is treated as suspect; the other as routine.

What magnifies the alarm in the Minnesota shootings isn’t just the loss of life, but the response that followed. Federal force was used against members of the U.S. public, and officials responded not with clarity or accountability, but with statements that collapsed under visual evidence. That willingness to lie, and to do so reflexively, signals a deeper problem: an administration increasingly willing to treat truth as an obstacle rather than an obligation.

A democratic society depends on shared facts. The right of citizens and journalists to observe, record, and document matters because it anchors truth in evidence, not authority. That right is not a threat to public safety. It is among the few remaining tools the public has to insist that power remains answerable to the truth.

Keep ReadingShow less

New co-owners of the Blue Door, Danny Greco, left, and Frank DiDonato, right, expect to open their new restaurant venture on Route 44, between Millbrook and Pleasant Valley, in March.

Photo by Aly Morrissey

PLEASANT VALLEY — La Puerta Azul, the Pleasant Valley restaurant known for its Mexican fare and live music, abruptly shuttered its doors at the end of 2025. The space is now set to re-open under new ownership and a slightly new name — The Blue Door Steakhouse.

The Blue Door is expected to open in March and will shift to an American and Italian menu, including pasta, steak and seafood dishes.

New owners Danny Greco and Frank DiDonato — both Hudson Valley residents — have worked together for the past two years across the street at Salt Point Market and Cafe. They described the new concept as “a familiar place, but elevated.”

Greco, who will manage all front-of-house aspects of The Blue Door while DiDonato will serve as the executive chef, said he is excited about the new venture. “It’s going to be rooted in community, inspired by tradition and thoughtfully refined,” he said.

Chef DiDonato began working at Salt Point Market and Cafe years prior to Greco’s 2023 purchase of the establishment. The two have since developed a close working partnership — one they joke began when Greco walked in for a sandwich and never left.

After learning La Puerta Azul had closed at the end of 2025, Greco and DiDonato moved quickly to pursue the space. They signed the lease on Christmas Day and described the timing as a gift.

“When I look at this space, I don’t see it under construction,” Greco said. “I see it open and running — and a place that feels like home to our community.”

The restaurant is currently undergoing a full interior renovation, but the new owners plan to preserve several elements as an homage to La Puerta Azul. The hand-painted bar tiles imported from Mexico will stay on the bar top, they said, and the waterfall at the entrance will also remain.

The pair also plans to preserve a wall mural titled “La Ballena/Long Bar” attributed to “A. Favela” and dated 2005.

In a nod to the building’s history, additional tiles left behind will be repurposed across the street at Salt Point Market and Cafe, where they will be used to accent a new pizza bar top. Greco and DiDonato say they want to extend the story of the previous restaurant beyond its original walls.

While the partners initially considered infusing Mexican flavors into the menu to honor the restaurant’s history, they ultimately decided to focus on what they know best.

“We realized that we should do what we know, and do it really well,” DiDonato said. “We want to give the community the best version of what we know how to do.”

Both owners said their approach is rooted in building trust locally — something they believe will carry over from their work at Salt Point Market and Cafe.

“You can’t just come into a small town and beat your chest,” Greco said. “People want to feel comfortable, and we believe that being a real part of the community is everything.”

DiDonato has built a local following for his culinary expertise, including meatballs, lasagna, and other Italian dishes. Regular customers ask what’s on the schedule and when certain items will be available.

Greco and DiDonato said The Blue Door will combine a playful, welcoming atmosphere with a serious focus on craft and hospitality.

The restaurant is expected to be open Wednesdays through Sundays from 3 p.m. to closing, with lunch services provided on the weekends. The owners will also accept catering requests and consider opening on Mondays and Tuesdays for private events.

With the opening still a month and a half away, the buzz is already strong. Former La Puerta Azul performers have reached out about returning for live music, and early social media comments — including questions about vegetarian and gluten-free options — have helped inform planning for the new menu.

“This was a busy restaurant before, and we believe it can be again,” Greco said.

The Blue Door is currently hiring for several positions and interested candidates can apply at contact@thebluedoorny.com.

Keep ReadingShow less

Amenia Town Hall on Route 22.

Photo by Nathan Miller

AMENIA — After nearly a month on the job, Dutchess County Legislator Eric Alexander, representing District 25, attended the Amenia Town Board meeting on Thursday, Jan. 22, to report on the work of the county committees to which he has been assigned.

“The legislature has switched to a Democratic majority,” Alexander noted, adding that Republican County Executive Sue Serino has said that she welcomes the opportunity to work in a bipartisan framework.

Alexander said that he will be serving as chairman of the Public Safety committee. Responsibilities will include Emergency Management Services (EMS) and the Sheriff’s department.

“It will give me a platform to set the agenda and focus on priorities like the growing cost of emergency care,” Alexander said, adding that he is seeking affordability options.

In response to a request by Gov. Kathy Hochul, each county will need to submit a comprehensive plan. Alexander said that the plan must include EMS service plans.

Having reviewed bids from three qualified locksmiths, the Town Board accepted the lowestbid, that of Stat Locksmiths of LaGrangeville to update the locks on Town Hall doors.

In other action the Town Board approved the hiring of a consultant planner to assist the Planning Board with projects under their consideration. The planner could also assist the Comprehensive Plan Committee with its updating process. The planner might also advise the Town Board on occasion, said Town Supervisor Rosanna Hamm.

Planning Board engineer John Andrews will be asked to draft a Request for Proposals document, used to solicit applications. The vote was unanimous.

Hamm reminded residents of the town’s overnight parking ban that prohibits on-street parking between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m. between Nov. 1 and April 1.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading