Students share work at Troutbeck Symposium

Students presented to packed crowds at Troutbeck.

Natalia Zukerman

Students presented to packed crowds at Troutbeck.

The third annual Troutbeck Symposium began this year on Wednesday, May 1 with a historical marker dedication ceremony to commemorate the Amenia Conferences of 1916 and 1933, two pivotal gatherings leading up to the Civil Rights movement.

Those early meetings were hosted by the NAACP under W.E.B. Du Bois’s leadership and with the support of hosts Joel and Amy Spingarn, who bought the Troutbeck estate in the early 1900s.

Students from Arlington High School in LaGrange, New York, Kara Gordon, Nicolas Giorgi, Justin Meneses Aquimo, Akhil Olahannan, and Sheik Bowden together with their teacher Robert McHugh, made the historical marker possible by pursuing a grant from the Pomeroy Foundation.

“We believe strongly that markers help educate the public, encourage pride of place, and promote historical tourism,” said the foundation’s research historian and educational coordinator.

The ceremony began with a land acknowledgement by students Kennadi Mitchell and Teagan O’Connell from Salisbury Central School who gave thanks to the Muncie Lenape, Mohican and Schagticoke people by saying, “This guardianship has brought us to this very moment where we may learn from one another. We honor and respect the continuing relationship that exists between these peoples and this land.”

The crowd was then welcomed by Charlie Champalimaud who, with her husband, Anthony are the current owners of Troutbeck. Speeches were then given by Kendra Field and Kerri Greenridge, co-hosts of the event and founders of The Du Bois Forum, an annual retreat of writers, scholars, and artists engaged in historic Black intellectual and artistic traditions.

Field noted, “It is our genuine hope that the dedication of new historical sites, most especially this one, as part of our larger commitments, will make more complex, more diverse, and more complete the answer to the simple question ‘what happened here?’ and the closely related question, “what might happen next for generations to come?’”

MaryNell Morgan enchanted the audience with her a capella renditions of several of Du Bois’s “Sorrow Songs.”

Du Bois used these songs as part of the presentation of his 14 essays in his seminal work “The Souls of Black Folk,” first published in 1903.

A graduate of Atlanta University where Du Bois taught twice, Morgan sang a medley of songs explaining that the best way to understand “The Souls of Black Folk” is to understand the songs. In attendance at the evening event were also local officials, Amenia Town Supervisor Leo Blackman, and New York Assembly Members Didi Barrett and Anil Beephan. Closing remarks were given by Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Associate Professor at Ohio State University and one of the panelists for the Symposium.

Over the next two days, more than 200 middle and high school students from 16 regional public and independent schools converged to present and discuss their year-long research projects, uncovering the often-overlooked local histories of communities of color and other marginalized groups, answering the questions posed the night before, “what happened here and what might happen next for generations to come?”

Rhonan Mokriski, history teacher and educational director for the Troutbeck Symposium, emphasized the student-led nature of the forum by saying the directive was to “give it to the students and let them run with it.”

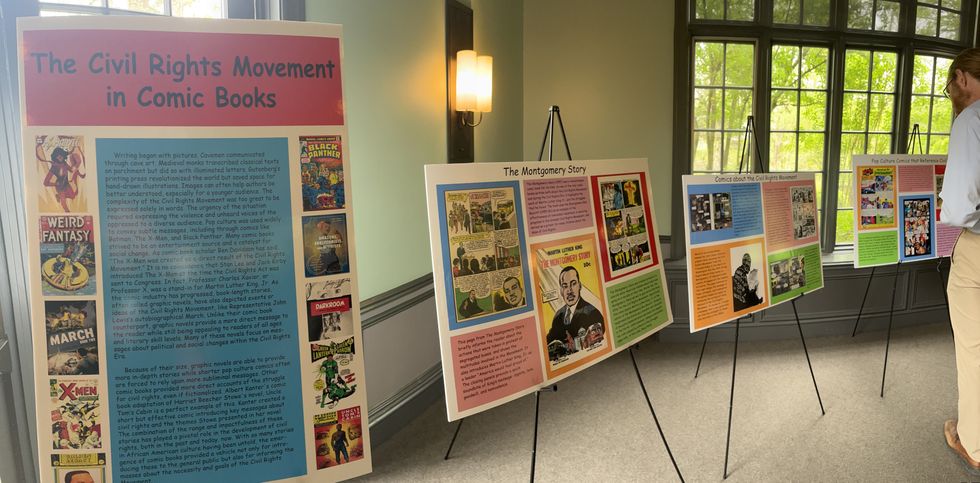

Through visual art, documentaries, personal and historical narrative, photographs, and multiple forms of storytelling, students skillfully presented their findings, revealing truths— often difficult ones—in the tradition of their predecessors who did so in the very same location.

Said Jeffries, “It’s one thing if the kids were doing research and then presenting in the, let’s say, school gymnasium, right? But to be able to do it here at Troutbeck, it adds the power of place and makes it all the more powerful.”

Student presentations ranged in topics from the Silent Protest of 1917 and its connection to the Amenia conference of 1916, the links between Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes and Nina Simone, to local families, Amy Spingarn’s quiet activism, reimagining Du Bois’s ‘The Crisis’ through a modern contextualization that included the recent Supreme Court action on Affirmative Action.

Jeffries and Christina Proenza-Coles, a professor at Virginia State University spoke after each set of presentations, responding to and contextualizing the students’ work.

“These projects themselves are commemorations,” Poenza-Coles said. “They are themselves peaceful protests that are pointing us to a more just future.” Poenza-Coles emphasized the interconnectedness of past and present and stated, “Spaces that we would have thought about as white spaces, in fact, were also black and brown spaces from the beginning of history. Histories are completely intertwined.”

Blake Myers, programming, marketing, and culture manager at Troutbeck spoke passionately about the community effort it takes to put on the event year after year. She said that while making sure the program is sustainable, “It really is a replicable model,” and hopes to see other institutions, schools, and foundations adopt it as a teaching tool.

The rooms, walls, and wooded paths of Troutbeck reverberated for three days with stories, past and present, celebrations and revelations of untold narratives and marginalized voices.

Said Jeffries, “America is a product of decisions and choices that were made, and often those were bad decisions and bad choices from the perspective of somebody committed to human rights and to equality. But that’s our foundation, that’s how we started this whole thing.

“So, you have that on the one hand, but then despite the systems of oppression that are designed to do just that, you always have people willing to fight against it and people who are willing to carve out spaces to preserve, promote and protect their own humanity.”

Left to grapple with the complexities of historical memory and its implications for contemporary society, Jeffries offered, “The work that’s being done here, connected with Troutbeck, it’s not just about recovery and discovery, which is critical. But then the question is what do you do with it (the information)? How do we commemorate?

“What do we put in place physically so that we don’t forget. Often, we think about history and this question of ‘if you don’t remember the past, if you don’t remember the systems that are created, then we are doomed or bound to repeat it.’ But we’re not going to repeat anything because most of the stuff, we never stopped doing.”

There was some laughter from the audience and Jeffries concluded, speaking to the students, “But you’re waking up, remembering, focusing, and bearing witness so that we can finally disrupt it. We can finally stop doing the things from the past that have created and generated inequality in the present by focusing on this community that is very much doing the work.”

MILLERTON – The Village of Millerton Board of Trustees will convene on Monday, Jan. 12, for its monthly workshop meeting, with updates expected on the village’s wastewater project, Veterans Park improvements and the formal recognition of a new tree committee.

The board is scheduled to receive an update from Erin Moore – an engineer at Tighe and Bond, an engineering and consulting firm – on the status of the village’s wastewater project. The presentation will focus on funding secured to date, as well as additional grant opportunities that may be pursued to support the long-term infrastructure effort.

Trustees will also discuss a proposed local law to formally establish a village tree committee, a group that has been in development for several months. The committee aims to improve the overall health and sustainability of Millerton’s trees, and plans to seek funding to support its work. An initial tree audit would be the first step in assessing the condition of existing trees, but the group must be officially recognized by the village to do so. The law will be discussed during Monday’s meeting and a public hearing will likely be set for a later date.

In addition, the board will review the State Environmental Quality Review (SEQR) process related to planned renovations at Veterans Park. Required by the state, this process will examine any potential environmental, social or economic impacts on the renovations that will be made to the park. In the works for more than a year, the renovations will include both landscaping and hardscaping improvements intended to enhance the space as a central gathering space in downtown Millerton. The work is funded through a Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) awarded in 2024. Village officials previously secured an extension on the grant, and construction is now expected to be completed by Memorial Day.

The meeting, which is open to the public, will take place at Village Hall at 5933 N Elm Ave. at 6 p.m.

Aimée Davis in her Millerton massage studio at 65 Main St. Davis offers massage therapy, relationship coaching and reiki in her studio and through home visits.

MILLERTON — While many view the new year as a starting line for resolutions and new habits, Millerton-based massage therapist and relationship coach Aimée Davis suggests a different course — a marathon, not a sprint. She believes a slower, more embodied approach can lead to greater fulfillment than ticking boxes off a list.

“I’m more of a daily-moment person,” Davis said, explaining that she focuses on small, consistent practices rather than big, rushed goals. Practicing conscious living year-round allows her to forego new year’s resolutions. “I made one yesterday and I’ll make one tomorrow — I’m constantly tracking what’s coming up, what’s drifting and what I want to change.”

As an intuitive healer, Davis has developed a deep appreciation for the human body over the years — and makes it her mission to help others do the same. “The body is so powerful — it’s just brilliant,” Davis said from her cozy, wood-paneled massage room in downtown Millerton.

Located at 65 Main St., the unassuming pink building is also home to naturopathic doctor and acupuncturist Brian Crouse. Davis laughs about their serendipitous meeting — which happened while she was eating a tomato sandwich — a chance encounter that eventually led to their shared workspace. Today, Davis is 12 years into her own practice, shaped by decades of training and experience in both bodywork and relationship counseling.

Although her work exists at the intersection of health and wellness, Davis is reluctant to embrace either label. “I’m in the business of people,” she said after a moment of reflection, adding that she believes there is a light inside of everyone.

Davis said she first discovered this light at age 18 when she worked at Berkshire Meadows, a facility for students with complex medical and developmental disabilities. She felt a pull to work alongside students with the greatest needs — many of whom were in wheelchairs and nonverbal. During this four-year period, Davis was responsible for feeding, bathing and bringing a sense of joy to these students. “We would play music and we became close like family,” Davis reflects on a period of her life when she stepped into the role of nurturer and caregiver. It was around this time that Davis also became a young mother.

The work and her role as a mother ignited a lifelong passion for learning about and supporting people. Davis said that, as a Capricorn, she tends to go all in when it comes to studying or understanding something. From training in chakras and reiki to studies in neurology, anatomy, and physiology, Davis has embraced lifelong learning and continues to see value in gaining knowledge from both peers and her community.

One mantra Davis lives by is “if it’s not a heck yes, it’s a heck no,” a mentality rooted in trusting intuition, being present, and coming back to your body. Each career stop has been a stepping stone to her current practice, which itself continues to evolve with the addition of relationship coaching and intuitive healing to supplement massage therapy.

Trusting intuition is core to her job, and was core to her following her own path. While it can feel scary to take a leap and start something new, Davis said she knew she was ready to put her “sunglasses on and jump into the bright abyss.” For anyone thinking about taking their own leap, Davis said, “the rhythm begins if you’re in alignment and doing what you’re meant to be doing.”

Today, she works with clients in a variety of ways — and no two sessions are the same. Davis said she has moved away from lengthy intake forms in favor of simply sitting with someone and meeting them where they are. “What I care about is how you are today,” she said, noting that what emerges in one session may look entirely different in the next.

While Davis is trained in anatomy, physiology and neurology — and works regularly with muscle tension, injury recovery and post-surgical care — she is also attuned to the emotional and energetic patterns that can surface in the body. She describes her approach as intuitive and often guided by things that are difficult to articulate. Information can come to Davis through sensation, temperature or imagery that arises as she works.

One early experience in her practice remains formative. Davis recalled working with a client whose blood tests suggested something was wrong, though no diagnosis had yet been made. While working near the client’s liver, Davis said she experienced a powerful and unsettling visual that gave her pause. Unsure how to proceed, she sought guidance from trusted mentors before eventually encouraging the client to pursue further care.

A later diagnosis confirmed liver cancer. More than a decade later, Davis continues to work with that same client and has at times served as a patient advocate, accompanying her to medical appointments.

While Davis is adamant that she does not replace medical care, she trusts what shows up. “I’ve learned not to ignore it,” she said.

As the new year unfolds, Davis hopes people will resist the urge to overhaul themselves overnight and instead consider what it might mean to slow down and build support. She encourages people to think in terms of a “care team,” recognizing that wellness does not have to take a single form.

“I just want people to give their wellness a better chance,” she said. For Davis, the work is less about resolutions and more about relationships — to the body, to one another, and to the rhythms that already exist beneath the noise.

“We still have choices,” she said. “And when we take care of ourselves, we’re better able to take care of each other.”

Eric Alexander stands in front of the Millbrook Diner on Franklin Avenue in the Village of Millbrook. Alexander was elected to represent District 25 in the Dutchess County Legislature.

MILLBROOK — Fresh off a narrow win in the race for Dutchess County Legislature, newly elected Eric Alexander — whose victory helped flip the county from red to blue — said the shift marks a “renewed commitment to good governance.” In November, Democrats took control of the legislature for the first time since 2008, and Alexander edged out his Republican opponent, Dierdre Houston, by just 41 votes.

A first-time candidate with an extensive career spanning communications and financial services, 69-year-old Alexander said, “To be able to start a new chapter at this stage of my life, I really hope I’ll be able to make a difference.”

Alexander — a first-generation American — is wrapping up his tenure as Board Chair of Emerson College, his alma mater. While on the board he has worn multiple hats, including chairing the Investment Committee and supporting the finance, audit and institutional advancement committees. Alexander gets a kick out of telling people he holds a “B.S. in Speech,” which he jokes will serve him well in politics.

Jokes aside, as his work in education winds down, Alexander is ramping up his own education as he gets up to speed on the requirements of the legislature and what will be expected of him. He plans to work with colleagues across party lines to benefit Dutchess County, with a particular focus on District 25, which includes Amenia, the Town of Washington, the Village of Millbrook, and Pleasant Valley.

“Bipartisanship brings good things like checks and balances,” Alexander said, adding that one-party leadership has led to wasteful spending and a lack of transparency within the county.

Alexander said he plans to judge his first year in office by whether the needs of rural communities are better understood across county government. “Broader and better awareness of the needs of this part of the county — that’s success,” he said, adding that a more collaborative process would also be an indicator of success.

He is also committed to “maximizing vertical integration of government,” meaning tighter coordination between town, county and state officials. Having met State Sen. Michelle Hinchey several times, Alexander said he will “unabashedly advocate” for constituents in his district.

He said housing, transportation and the EMS crisis are among the top priorities as he heads into the new year. Alexander is critical of the recent vote to spend another $2 million on supplemental ambulance services, which he described as a Band-Aid. “It’s kind of like trying to rent a solution,” he said. While the county-supported supplemental services improved EMS response time in some areas, Alexander said, “Not here — not in my town. So, that’s my job, to represent these communities.”

He also warned that the county’s growing reliance on private EMS providers like Empress — which is backed by private equity — could create long-term vulnerabilities. “Every year, we are the product and the client,” he said. “And we should consider being the competition.”

Though 12 months may not seem like enough time to achieve meaningful change, Alexander laughed, “Nothing is more motivating than a one-year term.”

Drawing on his communications experience — which played a role in his campaign — Alexander plans to keep constituents informed and engaged through a newsletter and social media content. He said, “I want to be very available and visible.”

Demolition crews from BELFOR Property Restoration began demolishing the fire-ravaged Water and Highway Department building in the Village of Millerton on Oct. 27, 2025.

MILLERTON — With another winter underway and new snow-removal equipment now in place, the village is reminded of the February morning when a fire destroyed Millerton’s highway and water department building on Route 22, wiping out everything inside and setting off a year of recovery and rebuilding. The blaze broke out in the early hours of Feb. 3, as snow covered the ground.

Demolition and planning

Nearly a year later, reconstruction efforts are ongoing. Demolition for the fire-damaged building began on Oct. 27, more than eight months after the fire broke out. The removal, which was completed by BELFOR Properties, marked a significant milestone in efforts to rebuild.

“It has been a work in progress that individuals have poured a lot of their time and effort into,” said Caroline Farr-Killmer, who was appointed as the fire project manager. She acknowledged that while it may have seemed like progress was slow, the process required thoughtful and thorough management. She added, “It’s not something that can be accomplished overnight — I am grateful for the team effort put in by all those involved.”

In the weeks after the fire, Farr-Killmer visited the charred site nearly every day, documenting damage to the structure and photographing debris to help the village rebuild its lost inventory.

Two new buildings on the horizon

The village plans to construct two separate buildings on the Route 22 site — one for the highway department and one for water operations.

The separation is now required by the Dutchess County Department of Health because a municipal water well sits on the property. Officials emphasized that Millerton’s water supply has remained safe. Weekly testing by VRI Environmental Services continues, with results submitted to the Department of Health.

BELFOR Properties is expected to handle the rebuild, though an official construction timeline has not been announced by the village.

A year of recovery

With a full lineup of new snow removal equipment, longtime Highway Department member Jim Milton said the crew is ready for the season. He credits Police Chief Joe Olenik with replacing inventory that was lost to the fire.

Olenik became highway superintendent on Sept. 26, following the resignation of former superintendent Peter Dellaghelfa. Although this winter will be his first leading the department, he brings extensive knowledge of village operations and already has a close working relationship with the crew. In the months immediately following the blaze, the village relied on borrowed equipment from the county and towns such as Ancram and Amenia.

The fire also destroyed Millerton’s police vehicles. Replacement Ford Interceptors — designed by Olenik and the Cruiser’s Division in Mamaroneck — arrived in early September. From February through September, Millerton officers used a loaned patrol car from Pine Plains.

To help the village manage the loss of space, the Town of North East signed an intermunicipal agreement allowing the Millerton Police Department vehicles to be parked at the town’s highway garage until the rebuilding is complete.

Record-setting year for firefighters

The fire marked the start of what became one of the busiest years on record for the North East Fire Company. In 2025, the all-volunteer department responded to more than 425 calls — the highest total in at least eight years.

Looking ahead, the Board of Fire Commissioners approved a $787,813 budget for 2026, representing a 2% increase, consistent with typical year-over-year growth.

The fire company enters 2026 with a mix of veteran and new leadership and a command staff that blends career firefighting, EMS expertise, and military experience. With an emphasis on rigorous training and a tight-knit culture, leaders say the department is positioned for a demanding year ahead.