Latest News

Costumed paraders

Nov 05, 2025

Nathan Miller

Webutuck Elementary students ushered in Halloween with a colorful parade around the school parking lot on Friday, Oct. 31, delighting middle and high school students who lined the sidewalk to hand out candy.

Legal Notices - November 6, 2025

Nov 05, 2025

Legal Notice

Brevi Properties LLC

Brevi Properties LLC, a domestic LLC, filed with the SSNY on 8/27/2025. SSNY is designated as agent upon whom process against the LLC may be served. SSNY shall mail process to 16 Peaceable Way Dover Plains, NY 12522. Purpose: Real estate management. Section 203 of the Limited Liability Company Law.

10-09-25

10-16-25

10-23-25

10-30-25

11-06-25

11-13-25

LEGAL NOTICE ANNUAL ELECTION OF THE Pine Plains

Fire District

On December 9, 2025

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the Annual Election of the Pine Plains Fire District will take place on December 9, 2025 between the hours of 6:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. at the Pine Plains Fire House located at 7 Lake Road, Pine Plains, New York 12567 for the purpose of electing one Commissioner: one Commissioner for a five (5) year term, commencing January 1, 2026 and ending December 31, 2030. Only residents registered to vote with the Dutchess County Board of Elections on or before November 16, 2025 and have resided in the Pine Plains Fire District for at least thirty days prior to the election, shall be eligible to vote.

Candidates for District Office shall file their names and the position they are seeking with the Secretary of the Pine Plains Fire District, Heather Lamont, P.O. Box 860, Pine Plains, New York 12567 no later than November 19, to 2025.

November 6, 2025.

BOARD OF FIRE COMMISSIONERS

PINE PLAINS

FIRE DISTRICT

11-06-25

Legal Notice

Silent Mind Apparel, LLC, Arts. of Org. filed with the Secy. of State of NY (SSNY) on 09/09/2025. Office location: Dutchess County, NY. SSNY designated as agent of LLC upon whom process against it may be served. SSNY shall mail process to: P.O. Box 593. Purpose: any lawful act.

10-02-25

10-09-25

10-16-25

10-23-25

10-30-25

11-06-25

LEGAL NOTICE

The South Amenia Cemetery Association Annual Meeting will be held Friday, November 07, 2025 at 7:00PM at 4007 Route 22, Wassaic, NY 12592 for the election of officers and trustees and the transaction of other such business as may legally come before it.

Amiee C. Duncan, Secretary

11-06-25

NOTICE OF

ANNUAL ELECTION

Wassaic Fire District in the Town of Amenia,

Dutchess County,

New York

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN, that pursuant to Section 175 of the Town Law, and other applicable statutes, an annual election of the Wassaic Fire District will be held on the 9th Day of December, 2025, at the firehouse located at 27 Firehouse Road, Wassaic, NY, between the hours of 6:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. for the purpose of electing the following:

ONE FIRE COMMISSIONER for a term of five (5) years commencing on January 1, 2026, and ending December 31, 2030; and

Each registered elector of the Town of Amenia who shall have resided in the Wassaic Fire District for a period of thirty days next preceding the election shall be qualified to vote at the election.

NOTICE TO CANDIDATES

Candidates must file their names with the Fire District Secretary on or before November 19, 2025. A candidate must be a resident elector of the Wassaic Fire District and registered voter in the Town of Amenia.

Dated: Wassaic, New York

November 5, 2025

BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF FIRE COMMISSIONERS OF THE WASSAIC FIRE DISTRICT in the Town of Amenia, Dutchess County, New York.

Fire District Secretary

11-06-25

Notice of Publication

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF

NEW YORK

COUNTY OF DUTCHESS

Index No. 2025-51557

FORECLOSURE SUPPLEMENTAL SUMMONS

LLACG COMMUNITY INVESTMENT FUND,

Plaintiff,

-against-

DONNA PARILLO, AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; BRENDA J. SWEENEY, AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF

EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; DONALD E. SWEENEY AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE

OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; EDWARD P. SWEENEY AS HEIR,

DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; JAMES

RICHARD SWEENEY AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P.

SWEENEY, DECEASED; ROSEMARY SWEENEY AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE

ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; SCOTT P. SWEENEY AS HEIR, DEVISEE,

DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; THOMAS SWEENEY AS

HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; RENEE PERRY AS HEIR, DEVISEE, DISTRIBUTEE OF THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY,

DECEASED; ANY AND ALL KNOWN OR UNKNOWN HEIRS, DEVISEES, GRANTEES, ASSIGNEES, LIENORS, CREDITORS, TRUSTEES AND ALL OTHER PARTIES CLAIMING AN INTEREST BY, THROUGH, UNDER OR AGAINST THE ESTATE OF EDWARD P. SWEENEY, DECEASED; NEW

YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TAXATION AND FINANCE; UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ON BEHALF OF THE INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE; “JOHN DOE #1- #50” and “MARY ROE #1- #50”, the last two names being fictitious, it being intended to name all other parties who may have some interest in or lien upon the premises described in the Complaint,

Defendants.

TO THE ABOVE-NAMED DEFENDANTS:

YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED and required to serve upon plaintiff’s attorney an answer to the complaint in this action within twenty days after service, or within thirty days after service is complete if the summons is not personally delivered to you within the State of New York. The United States of America, if designated as a defendant in this action, may answer or appear within sixty days of service hereof. If you fail to answer, judgment will be taken against you for the relief demanded in the complaint.

Trial is desired in the County of Dutchess. The basis of venue designated above is that the real property that is the subject matter of this action is located in the County of Dutchess.

NOTICE

YOU ARE IN DANGER OF LOSING YOUR HOME.

If you do not respond to this Summons and Complaint by serving a copy of the answer on the attorney for the mortgage company who filed this foreclosure proceeding against you and filing the answer with the court, a default judgment may be entered and you can lose your home.

Speak to an attorney or go to the court where your case is pending for further information on how to answer the Summons and protect your property. Sending a payment to your mortgage company will not stop this foreclosure action.

YOU MUST RESPOND BY SERVING A COPY OF THE ANSWER ON THE ATTORNEY FOR

THE. PLAINTIFF (MORTGAGE COMPANY) AND FILING THE ANSWER WITH THE COURT.

Dated: October 14, 2025

MCMICHAEL TAYLOR GRAY, LLC

By: s/ Patricia Pirri, Esq.

Attorneys for Plaintiff

3550 Engineering Drive, Suite 260

Peachtree Corners, GA 30092

(404)474-7149

10-23-25

10-30-25

11-06-25

11-13-25

Keep ReadingShow less

Classifieds - November 6, 2025

Nov 05, 2025

Help Wanted

Weatogue Stables has an opening: for a full time team member. Experienced and reliable please! Must be available weekends. Housing a possibility for the right candidate. Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531.

Services Offered

Deluxe Professional Housecleaning: Experience the peace of a flawlessly maintained home. For premium, detail-oriented cleaning, call Dilma Kaufman at 860-491-4622. Excellent references. Discreet, meticulous, trustworthy, and reliable. 20 years of experience cleaning high-end homes.

Hector Pacay Service: House Remodeling, Landscaping, Lawn mowing, Garden mulch, Painting, Gutters, Pruning, Stump Grinding, Chipping, Tree work, Brush removal, Fence, Patio, Carpenter/decks, Masonry. Spring and Fall Cleanup. Commercial & Residential. Fully insured. 845-636-3212.

SNOW PLOWING: Be Ready! Local. Sharon/Millerton/Lakeville area. Call 518-567-8277.

Local editor with 30 years experience offering professional services: to writers working on a memoir or novel, or looking for help to self publish. Hourly rates. Call 917-331 2201.

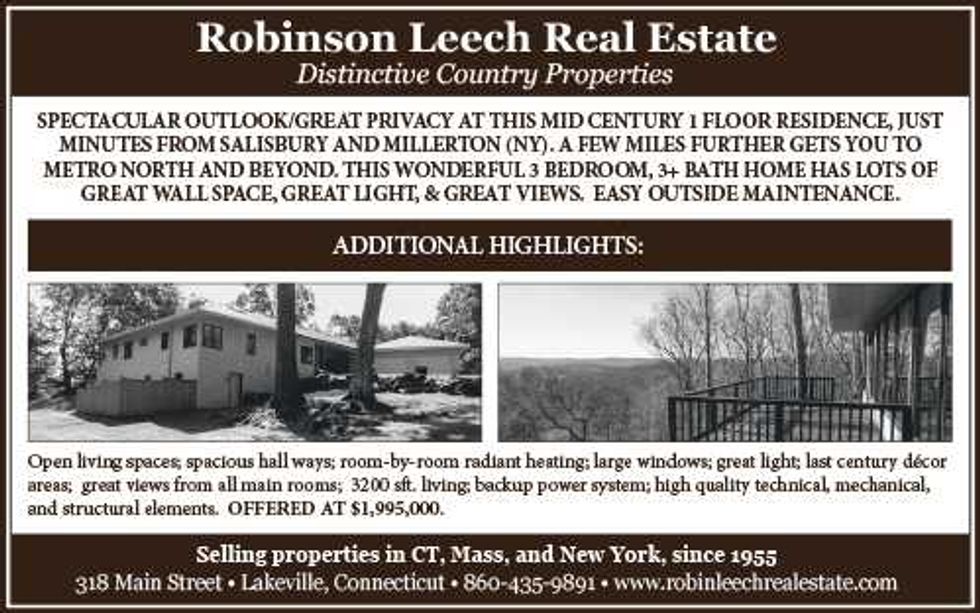

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Houses For Rent

Sharon, 2 Bd/ /2bth 1900 sqft home: on private Estate-Gbg, Water, Mow/plow included. utilities addtl. Please call: 860-309-4482.

Tag Sales

Falls Village, CT

Saturday November 8 Tag Sale in the Barn: 91 Main Street in Falls Village 10 to 3 pm. Please Park in town parking available along Main St. Tools, wood working tools, bench, furniture, antique doors, out door planters, Halloween and Christmas decorations and much more.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading