Latest News

Drivers should expect more police on the roads this weekend as law enforcement warns of ramped-up DWI check-points over Super Bowl weekend.

Photo by Aly Morrissey

Law enforcement is expected to ramp up DWI check-points across the region this weekend.

Across Dutchess County, local law enforcement agencies will take part in a “high-visibility enforcement effort” during Super Bowl weekend aimed at preventing drivers from operating vehicles under the influence of drugs and alcohol. Increased patrols and sobriety checkpoints are planned throughout the county from Sunday, Feb. 8, through Monday, Feb. 9.

In a statement, Dutchess County Executive Sue Serino emphasized the need for safe roads and thanked law enforcement who “work year-round to keep our neighborhoods safe.” She added, “Make the winning play during Super Bowl weekend and plan for a safe ride home.”

Nationwide, traffic fatality data indicates Super Bowl Sunday is one of the deadliest days of the year for impaired driving, with a significantly higher number of alcohol-related deaths than on typical Sundays.

During the Jan. 29 Village Board meeting, trustees voted to sign the annual STOP-DWI agreement with Dutchess County, part of a statewide effort to keep dangerous drivers off the roads. Similar efforts also take place around Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Halloween, Thanksgiving and during the December holiday season.

Millerton Police Chief Joseph Olenik said his department typically participates in all DWI check-points, but will not this weekend because of staffing issues. He said that does not mean county and state police will not be active in the Millerton area.

Keep ReadingShow less

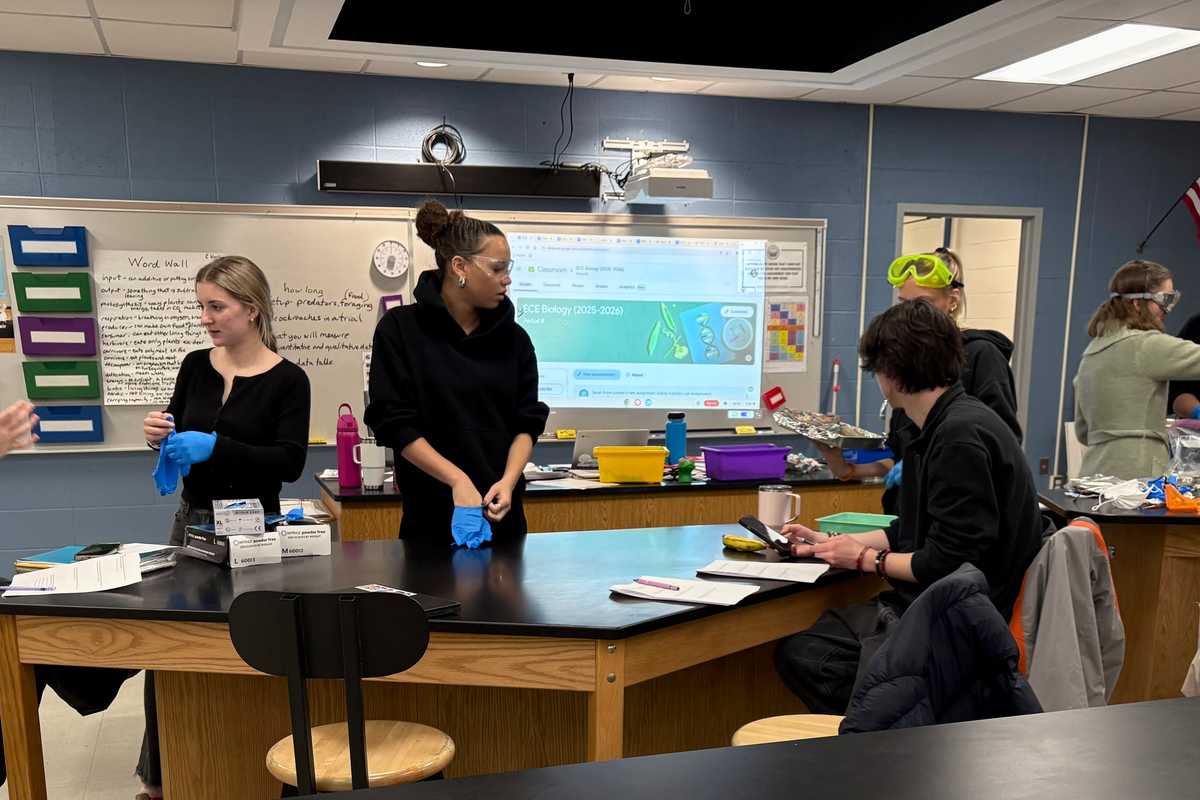

Students wore black at Housatonic Valley Regional High School Friday, Jan. 30, while recognizing a day of silence to protest Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Mia DiRocco

FALLS VILLAGE — In the wake of two fatal shootings involving Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in Minnesota, students across the country have organized demonstrations to protest the federal agency. While some teens have staged school walkouts or public protests, students at Housatonic Valley Regional High School chose a quieter approach.

On Friday, Jan. 30, a group of HVRHS students organized a voluntary “day of silence,” encouraging participants to wear black as a form of peaceful protest without disrupting classes.

The idea was spearheaded by junior Sophia Fitz, who said she wanted a way for students to express their concerns while remaining in school.

“What really inspired me was that I was feeling very helpless with these issues,” Fitz said. “Staying educated with what’s going on in not only our country but globally can be very stressful as a teenager. Kids right now are feeling very hopeless and want to do something, but don’t know how.”

Teachers Peter Verymilyea and Damon Osora were on board with the idea early on, describing it as a peaceful and respectful way for students to express their beliefs.

Assistant Principal Steven Schibi also backed the effort, emphasizing the importance of student participation.“I think it’s important for us to listen to students,” he said. “And they have to learn how to have a voice in such a way that it’s not disruptive.”

After discussions with Superintendent Melony Brady-Shanley and Principal Ian Strever, school administrators agreed that participation would be optional and that students could choose whether to wear black or not.

Schibi, along with several staff members, participated in the movement by wearing black themselves. Math department chair Kara Jones was among the participating teachers. “Everybody deserves their voice, so I’d rather do the day of silence than everybody stay home,” she said.

Among HVRHS students who supported the protest, at least one cited concern for friends affected by immigration enforcement.

Sophomore Peyton Bushnell said he felt anxious, fearing for the safety of friends and acquaintances. “I think it’s all really messed up,” Bushnell said. “I have a lot of Hispanic friends, and I worry if there’s ICE in Great Barrington, if they came here [and] deported my friends. I can’t even imagine.”

Bushnell said Fitz’s initiative encouraged him to speak more openly about the issue.

Senior Molly Ford echoed that sentiment. “I think it’s a peaceful way to protest and I think it’s the best way to do so,” Ford said.

Many students wore black to show support, and senior Victoria Brooks shared her thoughts on what it meant to her. “It means following along in a form of advocacy alongside other students,” Brooks said.

Some students declined to comment when asked about the protest. Others said they were unaware the protest was taking place. Three seniors interviewed during lunch said they would have participated had they known, calling it a “neat idea.”

Not all students were convinced of the protest’s impact. A group of juniors questioned whether it would make a difference.

“I think that it is good that we’re trying to do something,” one student said. “But I’m not sure how much the silence aspect of it will help, but I think that it’s good that we’re trying.”

Some students questioned the efficacy of the protests, including a group of seniors who offered their opinions. They expressed the belief that the protests were “pointless,” and that President Donald Trump probably didn’t even know that HVRHS existed.

“I just don’t think it’s the best way to go about it. Like, what is us being silent and wearing black gonna do,” one of the seniors said.

Senior Cohen Cecchinato voiced his opposition to the protests in another interview.

“The staying silent, I think, is for the lives that were lost, which I agree with,” Cecchinato said. “But I think that wearing black, like the movement that it’s behind, the people that are putting it into place in our school are doing it because it’s like the ‘F ICE’ movement or the abolish ICE movement, which I think is just wrong.”

Other students said they believed political protests don’t belong in school.

“I just don’t think we should bring politics into school,” one senior said. Another added, “I think it’s causing … a really big divide and people are using it to be advantageous to themselves and their own beliefs.”

However, one senior expressed a sharply critical view of the protest. Senior Ashton Osborne dismissed students who chose to wear black or participate in the demonstration and criticized organizer Sophia Fitz. He also said he strongly supported the federal immigration agency and added that if he were old enough, he would want to work for ICE.

The comments reflected a minority viewpoint among students.

Mia DiRocco, Hannah Johnson and Peter Austin are seniors at Housatonic Valley Regional High School and participants in The Lakeville Journal’s student journalism program, which produces HVRHS Today.

Keep ReadingShow less

The North East Community Center’s Early Learning Program shuttered abruptly last December after nonprofit leadership announced that significant financial strain required the program’s termination. NECC Executive Director Christine Sergent said the organization remains open to reconsidering childcare in the future.

Photo by Nathan miller

PINE PLAINS — Dutchess County Legislator Chris Drago, D-19, will host a public forum later this month to discuss ongoing childcare challenges — and potential solutions — facing families in Northern Dutchess. The discussion will take place on Wednesday, Feb. 25, from 6 to 7:30 p.m. at The Stissing Center in Pine Plains and is free and open to the public.

Drago said the goal of the forum is to gather community feedback that can be shared with county and state stakeholders, as Dutchess County positions itself to benefit from $20 million in state funding as part of a new childcare pilot program.

Earlier this month, Dutchess County was named as one of three counties in New York selected to participate in the pilot, which was announced by Gov. Kathy Hochul as part of a broader plan to bring universal childcare to the state. The funding is expected to support expanded childcare capacity, with a focus on infants and toddlers.

“We are inviting people who have expressed concern about childcare in Northern Dutchess, along with local school and faith-based program leaders, nonprofit organizations, and elected officials,” Drago said in a statement, calling childcare solutions a “critical need in our communities.”

The event follows the recent closure of the North East Community Center’s Early Learning Program (ELP), which left a number of families in Millerton and surrounding towns without childcare options — and left teachers without jobs. NECC announced the closure of ELP in early November and officially closed its doors on Dec. 18, 2025.

In a signal of support, Assemblymember Didi Barrett — who represents a largely rural district that covers parts of Dutchess and Columbia Counties — joined childcare advocates in the state capital last week to hear concerns from constituents. Barrett has praised recent state investments aimed at addressing childcare gaps, saying she will fight to ensure funds reach rural parts of her district.

“I am committed to ensuring that this is truly universal childcare and that the program addresses the childcare needs in Millerton, North East, and the surrounding communities, especially with the recent closure of the North East Community Center’s Early Learning Program,” Barrett said.

In December, Barrett secured $1 million in funding to expand childcare services at Dutchess Community College, and said she is committed to ensuring that new state funds will benefit those in rural communities.

Keep ReadingShow less

A Google Street View image of the former Pep Boys warehouse on Elizabeth Drive in Chester, New York, where the U.S. Department of Homeland Security plans to

maps.app.goo.gl

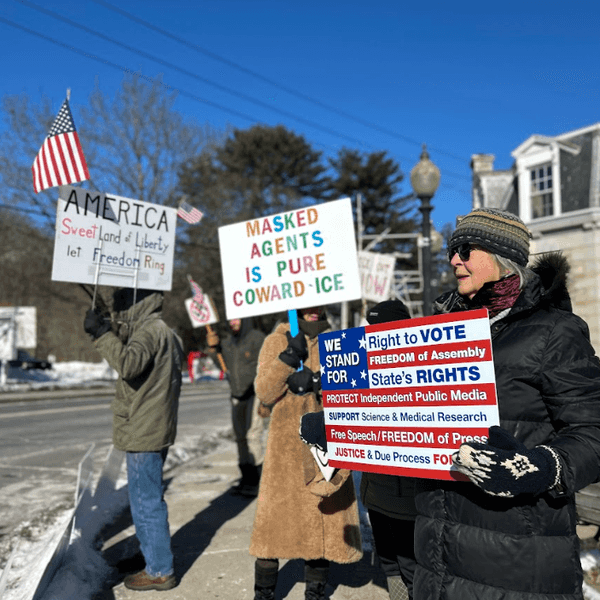

A proposed deportation processing center in Chester, New York, has sparked widespread backlash from local residents and advocates across the Hudson Valley.

The Department of Homeland Security issued a public notice on Jan. 8 outlining the plan, which calls for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to purchase and convert a warehouse at 29 Elizabeth Drive in Chester “in support of ICE operations.” The facility, located in Orange County, is a former Pep Boys distribution warehouse that was previously used to store tires and auto parts.

More than 400 people appeared at the Chester Village Board meeting on Jan. 12, according to a public letter addressed to ICE on the Village of Chester’s website, villageofchesterny.gov.

Village officials issued the letter on Jan. 16, formally opposing the proposal. The letter cited concerns about strain on the village’s sewer system, incompatibility with local zoning laws and a restrictive covenant governing the site.

Millerton village trustee Katie Cariello is among the local voices of opposition to the facility, sharing in a statement that she condemns the proposed detention center.

Dutchess County Legislator Chris Drago, D-19, also opposes the plans. “We must stop the development of an ICE detention center right in our backyard,” he said, in a statement. “With the horrific news continuing to come out of Minneapolis, we need to continue to make our voices heard and protect our neighbors.”

New York Senator Michelle Hinchey also denounced the plans. “The ‘warehousing’ language used by your agency to describe the detainment of human beings, and the subsequent mission of this proposal, is dehumanizing, abhorrent, and signals clearly the way your administration views American citizens and immigrants alike,” Hinchey said in a statement directed at the President.

She called the proposed facility a threat to the safety, values, and economic stability of Chester and the broader Hudson Valley community.

More than 20,000 people have signed a petition opposing the proposed facility in Chester that is sponsored by U.S. Rep. Pat Ryan, whose district includes Dutchess County, according to a statement from his office issued Thursday, Jan. 29.

The Jan. 8 public notice was required by an executive order dating back to President Jimmy Carter’s administration pertaining to floodplain management. The plan includes changes to the building’s interior, installation of a guard building, an outdoor recreation area, utility and stormwater improvements, and fence line changes, according to the public notice.

The proposed facility in Chester is part of a larger plan to adapt warehouses and industrial sites across the country into facilities that would hold more than 80,000 people total in a hub and spoke model meant to improve the efficiency of ICE’s deportation system, according to an ongoing Washington Post investigation originally published in December citing internal DHS documents.

Additional reporting by Aly Morrissey.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading